Such a potential reward explains the allure of other, still undeciphered scripts Robinson devotes a chapter each to eight of the most significant. The decipherment of the Mayans’ glyphs meant that their civilization could be studied as seriously as that of ancient Egypt or Greece. The resulting key wasn’t entirely reliable – one transcription was revealed to be the Mayan phrase for “I don’t want to say” – but it would help unlock the script four centuries later. Their decipherment owes much to the 16th-century Franciscan friar Diego de Landa who, despite torturing Maya and immolating their “diabolical codices,” bothered to quiz a nobleman about his writing system and jotted down some phonetic equivalents in Spanish. The Mayan glyphs look impossibly outlandish: cartoon-like animal figures squashed into geometric shapes and piled up like totems. When they were cracked in the 1970s, they allowed a new world civilization to speak for itself, rather than through the mouths of priests and conquistadors. The impact of the Mayan glyphs, Robinson shows, was very different.

This is the great peril of decipherment: you might spend years working out how to read a shopping list. Linear B, unfortunately, turned out to do little more than list names and goods. This “leap in the dark” paid off when he realized the underlying language was none other than Greek. Even then, the final conquest only came when Ventris began guessing at ancient Cretan place names. It took 50 years, though, for the 3,500-year-old alphabet to fall to the logical assault of the architect Michael Ventris, who devised a brilliant system of frequency analysis to work out which letters occurred where, and what parts of speech they might represent. Linear B was discovered in the 1900s, when clay tablets etched with scratchy letters started turning up on Minoan digs.

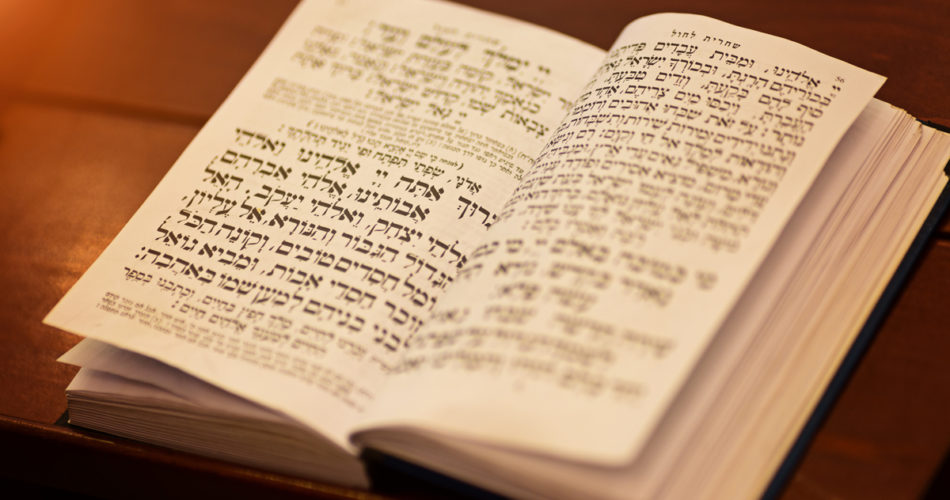

Hieroglyphs famously resisted decipherment for centuries, and were cracked only after a squad of Napoleon’s troops in 1799 came across the bilingual Greek/Egyptian Rosetta stone, set into an old wall in the Egyptian desert. (And splendid illustrations: the pages crawl with jaguar heads, ox’s feet and curlicues.)Īndrew Robinson begins with the stories of the three great decipherments: Egyptian hieroglyphs, Linear B and the weird glyphs of the Maya. It is a potent mix of academic esoterica, codecracking and controversy – the same giddy cocktail that made “The Da Vinci Code” such a success, but with much greater scholarship. This intriguing book on the strange art of “decipherment” focuses on those scripts that remain mysterious. The writings left on tombs and tablets by the great civilizations of the ancient past have mostly now been read.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)